The Geoengineering Dilemma: A Last Resort in the Climate Crisis?

The Geoengineering Dilemma: A Last Resort in the Climate Crisis?

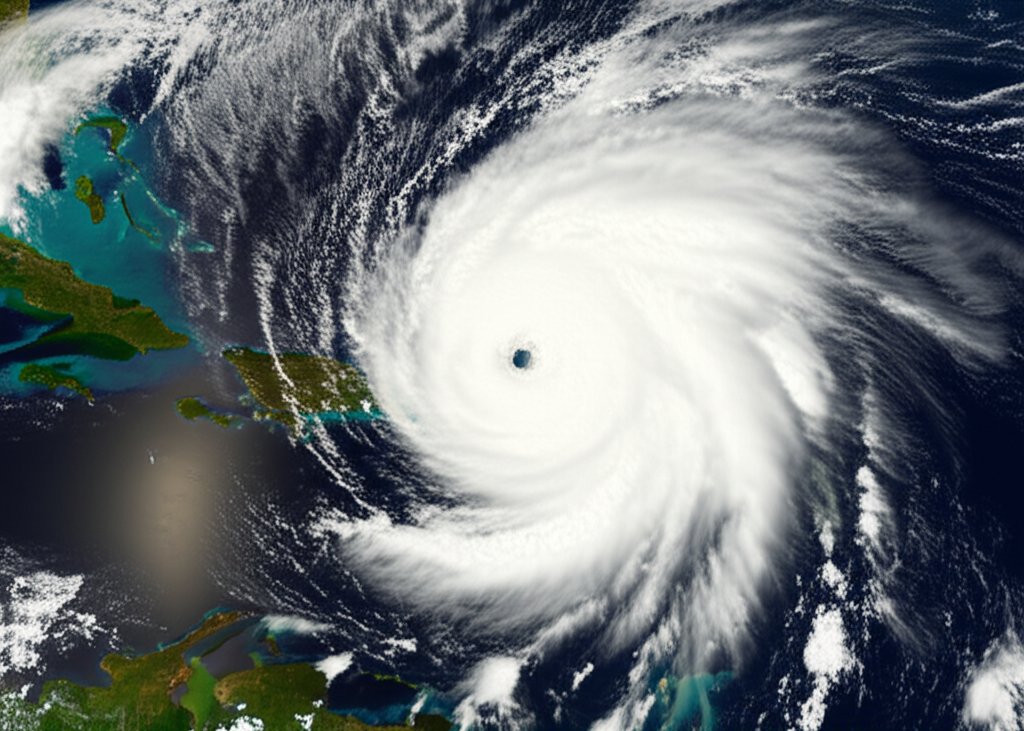

As the planet registers ever-higher temperatures, melting ice caps, and intensifying extreme weather events, the global community finds itself at a critical juncture. Conventional climate mitigation efforts, while crucial, are struggling to keep pace with the accelerating crisis. This dire reality is pushing a controversial "Plan B" into the mainstream discourse: geoengineering.

No longer confined to the fringes of scientific speculation, the deliberate, large-scale manipulation of Earth's climate systems is now a subject of urgent research and fierce debate among scientists, policymakers, and environmentalists alike. The question is no longer if we should consider it, but when, how, and who decides to deploy interventions that could have profound, unpredictable consequences for generations to come.

What is Geoengineering?

Geoengineering, or climate intervention, broadly refers to deliberate and large-scale interventions in the Earth's climate system to counteract global warming. It typically falls into two main categories:

- Solar Radiation Management (SRM): Aims to reflect a small percentage of incoming sunlight back into space.

- Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR): Focuses on actively removing CO2 from the atmosphere.

While CDR methods like direct air capture (DAC) or enhanced rock weathering are generally seen as less controversial and are more akin to mitigation, SRM technologies are the ones stirring the most heated debate due to their potential for rapid, widespread, and potentially irreversible effects.

Here’s a quick overview of some proposed methods:

| Category | Method | Description | Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solar Radiation Management (SRM) | Stratospheric Aerosol Injection (SAI) | Injecting reflective aerosols (e.g., sulfur dioxide) into the stratosphere to mimic volcanic eruptions. | Research phase; some small-scale field tests proposed/undertaken. |

| SRM | Marine Cloud Brightening (MCB) | Spraying fine sea salt particles into marine clouds to make them more reflective. | Early research; limited field experiments. |

| SRM | Space Reflectors | Deploying mirrors or other reflective materials in orbit to block sunlight. | Highly theoretical; extremely high cost and complexity. |

| Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR) | Direct Air Capture (DAC) | Using chemical processes to filter CO2 directly from ambient air. | Operational prototypes; high energy demand. |

| CDR | Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS) | Growing biomass, burning it for energy, and capturing/storing the CO2 emissions. | Research/pilot scale; land use concerns. |

| CDR | Enhanced Weathering | Spreading finely ground rocks on land or sea to absorb CO2 through natural chemical reactions. | Early research; scalability challenges. |

The Compelling Case for Intervention

Proponents argue that geoengineering, particularly SRM, might become a necessary evil to avert catastrophic climate tipping points, such as the collapse of major ice sheets or the irreversible loss of rainforests. With global emissions still rising and warming targets slipping out of reach, some see these technologies as a potential "emergency brake" to buy humanity more time.

"We are entering uncharted territory with climate change," warns Dr. Anya Sharma, a lead researcher at the Global Climate Intervention Institute. "While reducing emissions must remain our top priority, we cannot ignore the possibility that we might need tools to rapidly cool the planet if things escalate beyond control. It's a risk management strategy, not a solution."

Another argument posits that even if emissions were to cease tomorrow, the planet would continue to warm due to accumulated greenhouse gases. SRM could theoretically offer a way to rapidly reduce global temperatures within months or a few years, contrasting sharply with the decades or centuries required for CDR to have a similar cooling effect.

![]()

The Perils and Unknowable Risks

Despite the potential for rapid cooling, geoengineering is fraught with significant risks and ethical dilemmas. Critics highlight the moral hazard argument: the very existence of such a "Plan B" could reduce the political will to enact aggressive emissions cuts, fostering a false sense of security.

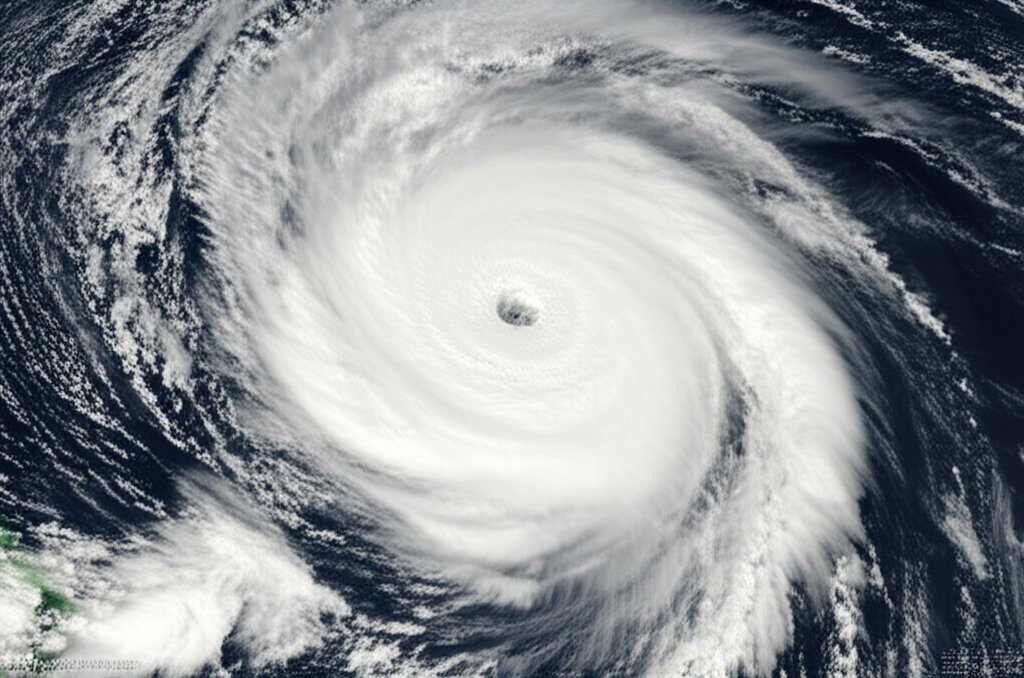

More concerning are the unintended consequences. Injecting aerosols into the stratosphere, for example, could alter rainfall patterns, potentially causing droughts in one region while exacerbating floods in another. Such changes could trigger geopolitical instability, food shortages, and mass migration. The science is complex, and current climate models cannot definitively predict all regional impacts.

"We are talking about planetary-scale experimentation with highly uncertain outcomes," states Professor Kenji Tanaka, an expert in climate ethics. "Who bears the risk if a geoengineering intervention causes crop failures in developing nations? The potential for weaponization or unilateral deployment by a single powerful nation also poses grave security concerns."

Furthermore, SRM methods like SAI would require continuous, long-term deployment. If abruptly stopped, the planet could experience a sudden, rapid rebound warming, known as a "termination shock," far more damaging than gradual warming.

![]()

The Governance Gap: Who Decides for the Planet?

Perhaps the most daunting challenge for geoengineering is the absence of a global governance framework. There is currently no international body with the authority to decide if, when, or how such technologies should be deployed. This creates a dangerous vacuum where unilateral action could have global repercussions.

"This is not a decision any single nation can make," emphasizes Ambassador Lena Kuznetsov, a climate diplomat. "The implications are planetary. We need robust, inclusive international agreements, frameworks for research, ethical guidelines, and mechanisms for accountability before any deployment is even considered."

Developing such a framework would require unprecedented global cooperation, navigating complex issues of equity, sovereignty, and responsibility, particularly given the disproportionate impacts climate change has on vulnerable nations.

![]()

Beyond the Band-Aid: The Imperative for Mitigation

Even as research into geoengineering continues, experts overwhelmingly agree that these technologies are not a substitute for aggressive decarbonization. They are, at best, a potential supplement or a last-ditch emergency measure. The only sustainable path to a stable climate is a drastic reduction in greenhouse gas emissions and a rapid transition to renewable energy.

The current debate surrounding geoengineering serves as a stark reminder of humanity's precarious position. It highlights the profound urgency to address the root causes of climate change and invest massively in sustainable solutions, rather than relying on high-stakes, planetary-scale gambles. The future of our planet may hinge on our ability to balance the desperate need for emergency tools with the fundamental imperative to stop the damage at its source.

[[IMAGE5]]